CW: Discussion of anti-Semitism

Introduction

Georgette Heyer is the critical link between Jane Austen and modern Regency romance. Case closed.

Case reopened. In the spirit of humility, I must admit: I hadn’t read any of Heyer’s works until last year—blasphemy! And in the spirit of keeping you subscribed, let me reassure you: I still know a lot about romance novels.

So, what makes Heyer’s works so significant? Writing between 1920 and 1974, Heyer essentially created the genre as we know it. Julia Quinn, the author of Bridgerton, refers to her as "the original." Inspired by Austen’s novels, she set her stories in Regency England. Unlike Austen, however, she wasn’t writing about her contemporaries. Et voilà—historical romance was born!

If a self-proclaimed literary authority like me once skipped straight from Austen to Quinn, it’s safe to say others have too. For newer or younger romance readers, Heyer’s works may be less familiar—even though it’s likely they have unknowingly read many books inspired by her.

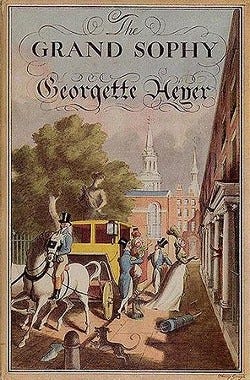

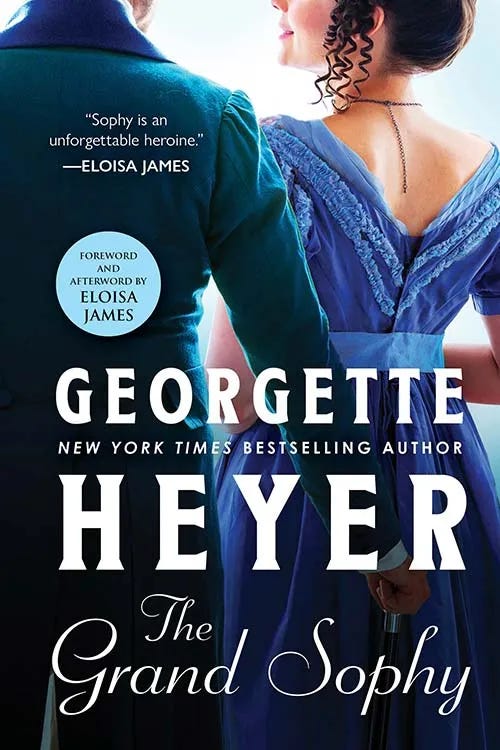

However, Heyer’s works are not without controversy. One of her most famous novels, The Grand Sophy, contains overtly antisemitic stereotypes and language. Whether that disqualifies her from your reading list is a decision only you can make. While there is much to admire and much to critique in Heyer’s work, her influence on the genre is indisputable. Her legacy forms the foundation upon which today’s historical romance is built. So without further ado let’s examine the Mother of Regency Romance - Georgette Heyer.

Biography

Georgette Heyer was born in London in 1902. Although she did not have much formal education, her parents encouraged all their children to read extensively. At seventeen, Heyer began crafting her first story as a way to entertain her younger brother Boris, who was bedridden from complications with hemophilia. Encouraged by her father, she wrote the tale down and submitted it to a publisher. Two years later, she published her debut novel, The Black Moth, at the ripe old age of nineteen.

Heyer’s brothers were not only the catalyst for her writing career but also a key motivation for her perseverance. After her parents passed away when she was only twenty-three, Heyer became the sole financial provider for nineteen-year-old Boris and fourteen-year-old Frank. Though Boris did get a job three years later, she remained the primary breadwinner for her family throughout her life. (Thank God I’m a younger sister.)

Style

Georgette Heyer’s style is well-known for painstaking period accuracy. Due to her copious research for her novels, she considered herself—and others did too—one of the greatest regency historians. Upon her death, she had accumulated over a thousand reference volumes ranging from the history of hair ribbons to price fluctuations of 18th century household goods.1

In a piece written for the Guardian in celebration of Georgette Heyer, comedian Stephen Fry writes “In the matter of period dramas it is a truth universally acknowledged that a period film or TV show tells you more about the period in which it is made than the period in which it is set.”2 He goes on to say that Heyer is the exception to this rule. Her writing is overflowing with period appropriate references, language, and sensibilities, with which an actual regency reader could not find fault.

“Heyer was meticulous in her description of Regency fashion, furniture, carriages, hunting, fencing, fist-fighting, gambling and domestic management. Her ephemeral detail helped to create a sense of the Regency that remains unmatched in fiction. Today her period dialogue has become a byword among historical novel readers and writers.” Jennifer Kloester, Georgette Heyer Biographer

Not everyone agrees with Fry. Marxist feminist, Lilian Robinson, thought it was a bit much - “passion for the specific fact without concern for its significance.”3 Heyer might have agreed, once stating that, “I ought to be shot for writing such nonsense.”4 As they say, one man’s literary masterpiece is another Marxist feminist’s regency encyclopedia.

Plagiarism Claims

Some of the best known early romance authors were accused of plagiarism by Georgette Heyer’s fans, cough Barbara Cartland. These keen-eyed readers eagerly reported their findings back to Heyer, noting the suspicious similarities. Heyer, who meticulously used primary sources like diaries and letters in her work, included references that would be difficult for others to replicate without direct copying. This made it glaringly obvious when phrases—and even character names—were lifted directly from her novels. Rumor has it she even invented a few terms to catch Barbara in the act.

Cartland was not particularly subtle, but despite having strong evidence, Heyer chose not to pursue legal action. Perhaps she was preoccupied, as she was frequently entangled in her own legal battles with tax authorities. Or maybe it was because, despite the blatant theft, Cartland still managed to mangle the details.5

Controversy

Modern discourse surrounding Georgette Heyer inevitably addresses instances of blatant anti-Semitism in her writing, most notably in The Grand Sophy. The prejudice in the text is unambiguous. The Grand Sophy was published in 1950, five years after the Holocaust—an event Heyer was well aware of—yet the novel's bigotry is glaring. This prejudice is further corroborated by Heyer’s personal correspondence, which weakens the argument that she was merely reflecting societal norms of the Regency period.6

The anti-Semitism in The Grand Sophy has been unequivocally condemned within the romance community. However, similar to the controversies surrounding contemporaries like Agatha Christie and Roald Dahl, there remains an ongoing debate about whether such works should be amended to remove offensive content. In 2023, the New York Times published an article, ‘You Can’t Hide It’: Georgette Heyer and the Perils of Posthumous Revision, in response to a newly edited version of Heyer’s The Grand Sophy.

The Heyer estate commissioned the edited version of The Grand Sophy, enlisting the help of famed novelist Mary Bly (pen name Eloisa James). However, when the estate declined to publish James’ afterword, contextualizing the edits and addressing the problematic aspects of the original text, James withdrew from the project. Like many, she felt that editing without transparency amounted to “reputation laundering”.

“They’re publishing a bowdlerized text, and I can’t have any part in that,” Bly said. “You can’t hide it.”

Despite her departure, the publisher, Sourcebooks, proceeded to release the edited version of The Grand Sophy, acknowledging the changes on the copyright page. They re-released a version including Eloisa James’ foreword and afterword in 2023.

Some readers strongly argue for preserving the original text and allowing individuals to interpret it within its primary context. Others advocate for updating novels to resonate with modern audiences and give them a renewed life. I believe that each reader should make their own decision. However, providing options and maintaining transparency are in my opinion positive steps.

Popular Works

When Frederica Merriville brings her three younger siblings to London determined to secure a brilliant marriage for her beautiful sister, Charis, she seeks out their distant cousin the Marquis of Alverstoke. Lovely, competent, and refreshingly straightforward, Frederica makes such a strong impression that to his own amazement, the Marquis agrees to help launch them all into society. Lord Alverstoke can't resist wanting to help her Normally wary of his family, which includes two overbearing sisters and innumerable favor-seekers, Lord Alverstoke does his best to keep his distance but he finally finds himself far from bored.

The Earl of Spenborough has always been noted for his eccentricity. Leaving Fanny, a widow younger than his own daughter Serena is one thing, but quite another is leaving his daugther's fortune to the trusteeship of Ivo Barrasford, marquis of Rotherham -- a man whom Serena once jilted and who now has the power to give or withhold his consent to any marriage she might contemplate. Lady Serena Carlow is an acknowledged beauty, many eager suitors have vied for her hand, but she's got a temper as fiery as her head of red hair. When her father dies unexpectedly, Serena discovers to her horror that she has been left a ward of the odious Lord Rotherham.

Devil’s Club (Alastair-Audley Tetralogy)

Duellist and gamester, the young Marquis of Vidal had fairly earned the sobriquet 'Devil's Cub' - a tribute to the wilder excesses of his father, the Duke of Avon.

When Mary Challoner discovered Dominic's plans to run away with her lovely sister, she donned cloak and mask in a daring impersonation and found herself bound for France with the most notorious rake in Georgian London.

Byatt, A. S. (August 1969), "Georgette Heyer Is a Better Novelist Than You Think", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary (ed.), Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, AL: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/oct/01/stephen-fry-on-the-enduring-appeal-of-georgette-heyer

Robinson, Lillian S. (1978), "On Reading Trash", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary (ed.), Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/30/books/georgette-heyer-romance-novel-antisemitism.html

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/oct/01/stephen-fry-on-the-enduring-appeal-of-georgette-heyer

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/oct/01/stephen-fry-on-the-enduring-appeal-of-georgette-heyer

I really want to write a regency romance series when I'm done with my current romantasy trilogy. Thank you for writing this so I know where and how the genre started.

I am glad I found your writing. I have to disagree with Stephen Fry. I am reading Sophy right now, and have read Arabella, and I am finding their references (especially to animals) very 1900s. It is a common trope in media from the 1900s to include animal companions who are adopted into a family and written about as a key element to a character's personality. For instance, Sophy has her array of pets and they are written about in an entirely different way and frequency than Austen would have. I have also noticed that Heyer's characters seem to reveal more of their emotional inner world (which I believe is a reflection of the time it was written then rather than the time it was written about." I know I will find more occurrences as I read and pay attention.